System of climate injustice

Taking Action Towards Climate Justice

- Article, Research

In 2015, 195 countries agreed as part of the Paris Agreement to limit global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius by the year 2100, and to pursue efforts to keep it within the safer limit of 1.5 degrees Celcius. If successful, this means that by the year 2100, the average surface temperature of the planet would have risen by no more than 1.5 degrees Celcius since pre-industrial times. Despite the urgent calls from the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) as well as other scientists, journalists, activists and other concerned citizens, governments and large corporations have been criticised widely for not taking drastic action to ban fossil fuel extraction and limit emissions of greenhouse gases.

Ressource

- The UNPD Climate promise website gives useful overviews of its key activity areas: adaptation and resilience, carbon markets, circular economy, climate finance, climate security, energy, forests, lands and nature, inclusion, just transition, loss and damage, net zero pathways, transparency, and urban issues.

- Project Drawdown draws on world-class network of scientists, researchers, and fellows, and has characterised a set of 93 technologies and practices that together can dramatically reduce concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. of resources for climate solutions.

- One section of the Project Drawdown website is Drawdown stories which leverages storytelling and engagement as a bridge between science-based climate solutions and everyday people looking to find their roles in stopping climate change.

- Another resource from Project Drawdown is the Toolkit to help people to recognise how every job is a climate job.

- To view live updates on the amount of time left to keep warming under 1.5 degrees Celcius – visit the Climate Clock

- To view live updates on the amount, in parts-per-million, of carbon dioxide in our planet’s atmosphere, visit Per Million

- For simple definitions across a range of relevant climate terms, search the United Nations Development Programme’s Climate Promise Climate Dictionary (This is the link to the English language version but it is also available in Spanish, French, Arabic, Russian, Turkish, Thai and Mongolian.)

- Climate Learning resources by the STEM Teaching Tools project, by the University of Washington Institute for Science + Math Education.

- Future-oriented learning for inclusive science education: teaching and learning resources for secondary education. (Erduran & Ioannidou, 2023). The resource pack contains materials for science teachers and secondary pupils, and aims to support lessons on climate change that include timely and pressing issues related to science and society, including gender-related issues and green careers.

The GreenComp Framework published by the European Commission in 2022 is a reference framework for sustainability competences. It provides a common ground to learners and guidance to educators, advancing a consensual definition of what sustainability as a competence entails. To move towards regenerative, sustainable futures in which humans live in reciprocal relationships with the Earth, LEVERS adopts this multi-species outlook on sustainability as proposed by the GreenComp Framework “Sustainability means prioritising the needs of all life forms and of the planet by ensuring that human activity does not exceed planetary boundaries”.

The GreenComp Framework involves four key competence areas:

- Embodying Sustainability Values

- Embracing Complexity in Sustainability

- Envisioning Sustainable Futures

- Acting for Sustainability

Educators in the EU are encouraged to join the GreenComp Community hosted by the European Commission’s Education for Climate Coalition. This is an online community of people and organisations using the framework to develop knowledge and skills to live, work and act sustainably. As well as hosting events for the entire network, it also includes countrylevel groups for EU member states.

As extreme events including floods, droughts, heatwaves and wildfires impact increasingly greater swathes of society across the globe, the urgent need for climate action is becoming ever more pronounced.

While responses have often been considered to be in the realm of the scientific, technological or financial, increased attention is being paid the ways that “climate change impacts people differently, unevenly, and disproportionately as well as redressing the resultant injustices in fair and equitable ways.” (Sultana, 2021, p. 118). A core tenet of climate justice is the integration of social and economic factors into climate solutions.

The focus cannot only be on scientific approaches to combatting climate change and environmental degradation, it must also address the social and economic inequalities with which climate issues are so intimately intertwined.

This is in part because of the unequal historical (and contemporary) responsibility and burdens that communities bear: countries, industries, and businesses that have become wealthy from activities that emit the most greenhouse gases do not experience the effects of climate change as acutely as the most vulnerable communities who often have contributed the least to the crisis.

These countries, industries, and businesses therefore have a responsibility to urgently move towards sustainable practices, and to address the prior damage caused through fair and equitable measures of redress.

Climate action is the active participation in strategies to address the climate crisis, with the inclusion of considerations of the economic and social factors in climate problem-solving. Climate action can help to relieve the underlying causes of conflict and insecurity, creating a more just and liveable world for everyone. It begins with the acknowledgement that the climate crisis does not affect everyone equally, and that those most at risk are those who have contributed to the creation of this crisis the least.

Young climate activists are becoming increasingly vocal in the climate struggle. Children and youth today have not contributed as much to anthropogenic climate change compared to previous generations, but will bear the full force of current and future climate change impacts as they advance through their lifetimes. The human rights of today’s younger generation are threatened by the decisions of previous generations, and therefore they must have a central role in all climate decision-making and action. It is their future to inherit.

Ressources

Case Study - Pacific Island Students Fighting Climate Change

For an example of youth climate activists acting to protect their human rights, read about the Pacific Island Students Fighting Climate Change, which played a key role in the passing of the Vanuatu Resolution.

An example of a science institution championing youth voice in the climate struggle is the Generation Hope programme of the National History Museum (UK). This annual programme is developed and delivered in partnership with young climate activists and advocates from around the world. Recent editions have featured climate justice campaigners Mitzi Jonelle Tan and Clover Hogan.

One youth campaigner using the arts and appeal to emotion to spread her message of climate activism is Louise Harris, with her music video “We Tried” which reached #4 in the 2023 UK Christmas charts.

Read - Climate Action to Transform Our World by youth climate activist Mikaela Loach

It’s Not That Radical: Climate Action to Transform Our World by youth climate activist Mikaela Loach (2023)

A field guide to climate anxiety: how to keep your cool on a warming planet by Sarah Jaquette Ray

Indigenous and traditional knowledge and practices

Colonialism is another thread with which environmental action is entangled. Colonialism has played an important role in the degradation of the environment, and its persistent impact across the world continues to hinder climate initiatives in several ways. Colonial powers were often made rich upon environmentally harmful industrial projects, but they were also responsible for the suppression of non-Western knowledge and knowledge-making practices that are beneficial to understanding and generating more caring and localised approaches to environmental issues.

Ressources

Read - Max Liboiron's "Pollution is Colonialism"

In Max Liboiron’s 2021 work, “Pollution is Colonialism” the author explores the entanglements between capitalism, colonialism, and environmental science. Liboiron contends that the consequences of environmental contamination echo the power dynamics of colonialism, where certain groups bear the brunt of ecological harm while others benefit from resource extraction and industrial practices.

This perspective prompts a critical examination of environmental justice, urging us to recognise pollution as a manifestation of systemic inequalities rooted in historical colonial structures that persist in shaping contemporary environmental challenges, and to consider specifically situated ethical, and relational approaches to science and science education.

Read: In Conversation with Max Liboiron: Towards an Everyday, Anticolonial Feminist Science (Education) Practice – a chapter in the open access book Reimagining Science Education in the Anthropocene, Volume 2, edited by Sara Tolbert, Maria F.G. Wallace, Marc Higgins and Jesse Bazzul.

Watch: Max Liboiron discussing anticolonial science as part of Academy for Teachers Master Classes.

Watch - Max Liboiron discussing anticolonial science as part of Academy for Teachers Master Classes.

Consumption and Economic Models

Capitalism plays a central role in the climate crisis as the pursuit of profit often prioritizes short-term gains over long-term environmental sustainability. The relentless exploitation of natural resources and the reliance on fossil fuels within capitalist systems contribute significantly to greenhouse gas emissions, exacerbating global warming. Additionally, the profit-driven nature of capitalism can hinder the adoption of environmentally friendly practices and policies, creating challenges in addressing the urgent and interconnected issues of climate change.

The concept of degrowth specifically re-examines the predominant understanding of economic growth – that it is the only answer for human progress to continue apace. Instead, degrowth proposes a deliberate reduction in consumption and production.

In his 2020 book ‘Less is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World’, economic anthropologist Jason Hickel advocates for this shift by emphasizing that environmental unsustainability furthers economic inequality. He suggests that by prioritising wellbeing and an equitable redistribution of resources, a way towards a more balanced world both ecologically and societally is possible. Hickel points out that the indicators of happiness or citizens’ sense of meaningfulness are not in direct proportion to a nation’s wealth. Instead, it is how that wealth is distributed that effects these less-easily quantifiable indicators of a society’s cohesiveness.

These social implications are also directly related to a society’s interactions with and impact on the environment. Hickel points out that by investing in public services – a direct social good – can also have ecological benefits. He states, “Public services are almost always less intensive than their private equivalents” (Hickel 2020, p. 237-8). He gives the example of the British National Health Service, which “emits only one-third as much CO2 as the American health system”, while also providing better and more equitable care. This clearly links societal care and positive ecological outcomes that can be achieved when economic focus is not placed solely on economic growth at the expense of all other living things and the planet.

Ressources

Ressource - Doughnut economics

Ressource

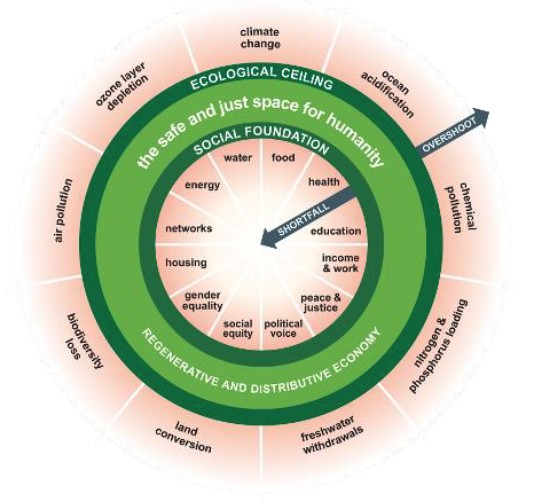

Doughnut economics is a visual representation of an economic and social sweet spot, first conceptualised by Kate Raworth in her 2017 book ‘Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist’. The Doughnut consists of two concentric circles: the inner one represents a social foundation where everyone has access to life’s essentials (as outlined in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals) while the outer ring represents the ecological boundaries that our planet can sustain. Between these two boundaries (the doughnut shape) is the ecologically safe and socially just space within which humanity can survive, a Goldilocks zone of human interaction and inclusive, sustainable, economic growth.

Doughnut economics calls for a move away from GDP as a measure for growth towards regenerative and restorative futures, but it is also an economic model which does not rely on the complete rejection of capitalist consumption patterns. Doughnut economics is a suggestion for mitigating the impact of those impulses, as opposed to a direct push against it in the way advocated by proponents of degrowth.

To change the futur, change the dynamics

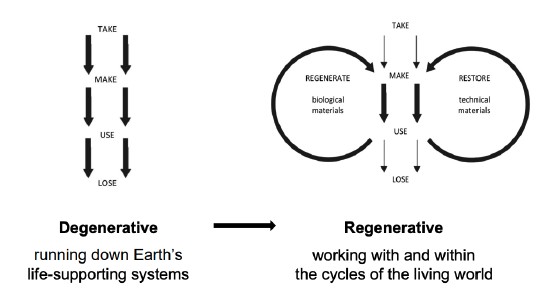

From a degenerative to a regenerative and restorative circular economy. Image reproduced from Doughnut Economics Action Lab.

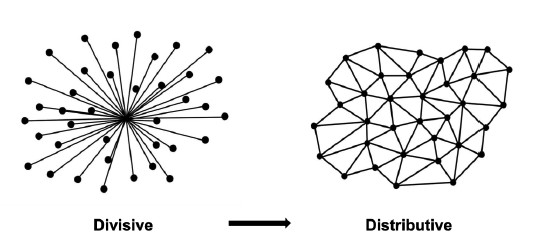

From a divisive to a distributed economic model. Image reproduced from Doughnut Economics Action Lab.

Case Study - Amsterdam’s municipal government has integrated doughnut economics

Amsterdam’s municipal government has integrated doughnut economics into its governance, with an eye towards being completely circular in its economy by 2050. This will include a 55% CO2 emission, 50% reduction in new raw material use by 2030, and have 100% circular procurement processes with a 20% reduction in public consumption by 2030 (Reid 2021, Municipality of Amsterdam 2020).

Amsterdam Municipality has committed to prioritizing purchasing products and services that are environmentally friendly, durable, and reusable, themselves through the official procurement processes while also encouraging the local producers to move towards goods that also align with circular economics, moving closer towards the Doughnut model. Amsterdam has been actively supporting collaboration between business sector actors, researchers, and community stakeholders to develop workable solutions that will contribute to a circular economy.

The government has provided funding, facilitated events, and generated platforms for knowledge sharing. These hubs and networks are designed to bring together stakeholders from all sections to accelerate the movement towards a circular economy through Doughnut Economics (Reid 2021). The initiative focused on closing the loop of resource streams, starting with nine main resource streams: biomass, construction and demolition materials, electronic and electrical waste, end-of-life textiles, plastics, diapers, mattresses, data servers, and metals. These streams were identified because of their high volume and significant environmental impact.

Then came the implementation, which occurred in six steps (Cramer 2020a):

- Collect insights. Meetings with experts, literature reviewed.

- Brainstorming. Based on the experts’ insights, representatives of the value chain of each stream were included in sessions to generate options of closing the loop from a technical, practical, and economic perspective.

- Consulting the market. Investments were solicited and the conditions under which they could be acted upon, explored.

- Investor selection. Once market players expressed interest, an independent party judged which would be the best candidate. After the selection process, a consortium was set up to bring the initiative to fruition.

- Creating the preconditions. For the consortium to work smoothly, a number of preconditions were necessary, and the Amsterdam Municipality Economic Board assisted in cooperation with authorities to generate them. Each initiative needed an appropriate collection and logistics system, guaranteed amounts of waste, specific demand for the recycled material, and quality standards.

- Action-plan. Generation of a plan of action which included timelines and investment schemes, and the clearly defined functions and responsibilities of each consortium member and other relevant actors.

RELFECTIVE QUESTIONS

- What does a “just transition” mean in your locality?

- Can you identify some organisations who work specifically on topics related to climate justice or just transition?

- How can your Learning Venture make a link between just transition and science education in your locality?